A title can make a film, and Night and the City is the perfect title for a film noir. It is a distillation of two of the most iconic elements of film noir, a genre that flourishes in the encroaching darkness and the unfeeling industrialism of cityscapes. Those four words conjure the immoral horrors of a corrupt city with a life of its own. In the case of Jules Dassin’s Night and the City, the city is London, and it’s overrun with hustlers and conmen. The first film Dassin made after being exiled from America for alleged communist sympathies, Night and the City is an amalgamation of film noir and its origins. Directed by an American, starring American and British actors, shot by German cinematographer Max Greene, and borrowing from both the American studio system and British pulp-thrillers, the film serves as a unique hybrid of film noir’s cinematic roots.

The ever-disturbing Richard Widmark stars as the American hustler Harry Fabian. He is constantly investing money in get-rich-quick schemes and trying in vain to make something of himself. Inevitably, he finds himself running from his debts and stealing a few pounds here and there from his long-suffering girlfriend, Mary Bristol (Gene Tierney). Harry and Mary both work for the Silver Fox nightclub run by Phil Nosseross (Francis L. Sullivan) – Mary as a singer, Harry as a scam artist who draws unwitting patrons to the club. During one of his trips out to pick up new customers for the Silver Fox, Harry happens to meet the former wrestling champion, Gregorius, and seizes his chance to begin another scam. Gregorius’s son, Kristo, has a monopoly on wrestling in London but only promotes a new style of professional wrestling, as opposed to his father’s forte, classic Greco-Roman wrestling. Harry believes that he can surreptitiously take over wrestling promotion in London by manipulating Kristo through his father.

Very much a product of the fear surrounding McCarthyism, Night and the City might not exist were it not for Dassin’s left-wing politics. In 1949, Dassin was sent to London to avoid scandal within Twentieth Century Fox and then began work on Night and the City. The finished film reflects this hectic state of affairs. More so than any previous Dassin film, Night and the City erupts with unyielding pessimism and anger, and its characters are hateful and resentful; ambition their driving force. The film depicts London as a nightmarish place. So committed was Dassin to this presentation that he insisted on night-for-night filming, with illuminated shop windows as the only light source. Cloaked in shadow and populated solely by the most desperate of people, Dassin’s London is a hell of the living.

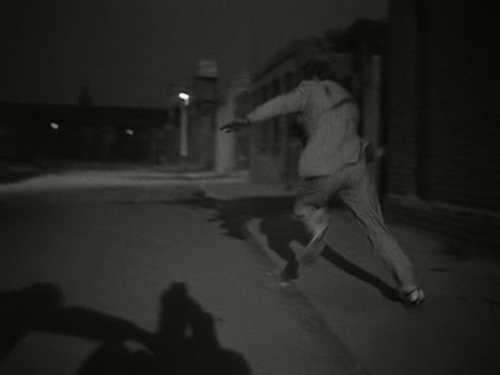

From the very opening scene, Dassin’s protagonist, Harry Fabian, is portrayed as a vulnerable and ultimately doomed man. He is first shown running for his life from a man we never see. Likely, he is running from loan sharks or debt collectors, whoever he’s managed to anger this time. And once Harry reaches Mary’s flat, his ability to shrug off this race through dark alleyways tells us in no uncertain terms that this has happened many times before and will happen again because Harry is constantly out to find a way to earn a living and “become somebody.” This clues us in on Night and the City’s biggest theme: the destructive nature of ambition. Harry’s life revolves around money and the scams that may make or break him. Mary sums up the disappointing life that Harry has led saying, “Harry, you could have been anything. Anything. You had brains…ambition. You worked harder than ten men. But the wrong things. Always the wrong things.” The film is relentless in showing just how far Harry has overreached with his Gregorius wrestling scam. While Harry’s goals are commendable – to lift himself out of the seedy world of crime – his fate is set from the beginning. Just as he ran for his life at the start of the film, Harry finds himself running once again and ultimately being strangled by one of Kristo’s men and thrown into the Thames. This dark, fatalistic ending marks Night and the City as one of the bleakest films produced by a Hollywood studio.

This bleakness extends to the characters in Night and the City in that they are all strikingly unsympathetic. Even the darkest of film noirs includes a character for the audience to sympathize with, but Harry’s demise is perfectly justified, given his actions. The film as a whole lacks any real sentimentality in regards to its subjects. This isn’t your typical Hollywood film where the bad guy dies, the good guys win, and order is restored. If anything, the end of Night and the City sees a good man die senselessly, a bad man get what was coming to him, and the established racketeers maintain control. However, Harry’s story does take on some elements of tragedy. In trying to make something of himself, Harry moved out of his closed world of crime and ultimately died for it. Yet despite the twinge of sympathy one might feel for a man who couldn’t better himself, it is all too clear that Harry’s death was the result of his own misguided actions. In many ways, Harry was delusional thinking he could simply take over from men like Kristo and Phil. He even believes in his final moments that he was “so close to being on top,” when, in fact, he had never come near those heights.

Despite having to oversee the film’s post-production by phone because of McCarthy and the Hollywood blacklist, Dassin created a cohesive and exemplary film noir. While Night and the City follows noir narratives and archetypes perfectly, it still manages to capture a unique cynicism in its story. The fatal resolution keeps with the dark genre, but Dassin delivers the scenes of Harry’s final moments with little emotion. This defeatism singles out Night and the City as one of noirs best offerings.