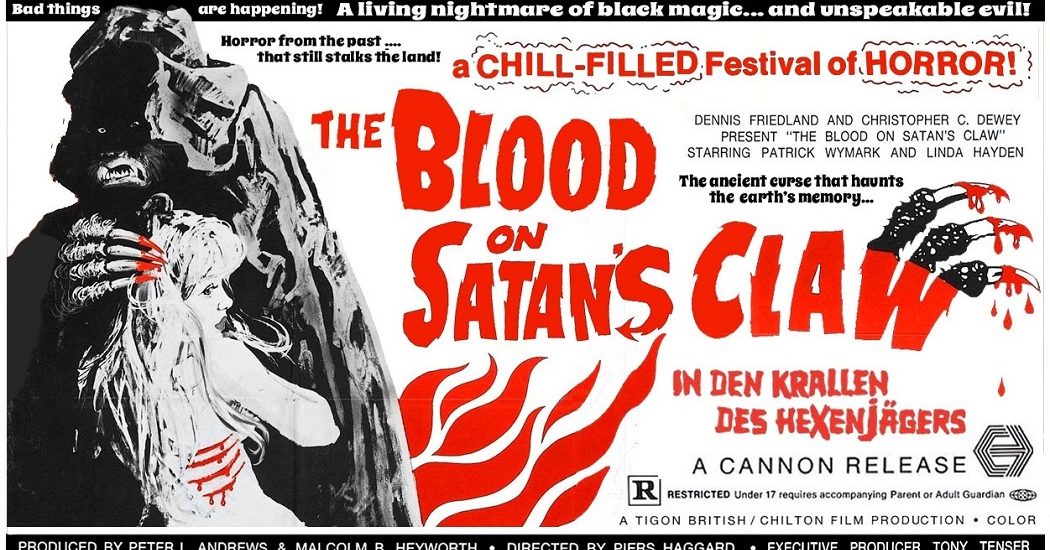

Cinema Fearité presents 'The Blood on Satan's Claw''

Cinema Fearitétries to get to the bottom of Folk Horror with 'The Blood on Satan's Claw.'

Ari Aster’s Midsommar (which is, by the way, one of the best movies of the year) has got everybody talking about “Folk Horror.” But what is that? Generally, Folk Horror derives its themes and subjects from folklore or mythology, usually with a basis in religion, but not always. Of course, movies like The Wicker Man and The Witch come immediately to mind, but movies like Witchfinder General and Picnic at Hanging Rock fit the mold, too. And so does 1971’s creepy The Blood on Satan’s Claw.

The Blood on Satan’s Claw begins with a farmer named Ralph Gower (Barry Andrews from Dracula Has Risen from the Grave) finding what appears to be a hairy human skull on his farm. He reports the discovery to the local Judge (Repulsion’s Patrick Wymark), but the remains disappear by the time they return to investigate. But the damage is done; evil has been released upon the village. First, a young gal named Rosalind Barton (Tamara Ustinov from Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb), the fiancée of Peter Edmonton (Simon Williams from The Fiendish Plot of Dr. Fu Manchu), gets possessed by an unworldly force. Then, the students of the Reverend Fallowfield (Naked Evil’s Anthony Ainley) start acting erratically, with some of them winding up hurt and dead. The Judge deduces that the village’s troubles all stem from a coven formed by the seductress Angel Blake (Linda Hayden from Taste the Blood of Dracula), and he rallies the troops to defeat the evil before it conquers the town.

Director Piers Haggard (Conquest, Venom) worked very closely on the script for The Blood on Satan’s Claw with screenwriter Robert Wynne-Simmons (The Outcasts). Finding influence in everything from classic Hammer Horror and fellow folk horror movies like Witchfinder General to the real-life treachery of the Manson Family and the Mary Bell murders, Haggard and Wynne-Simmons carefully crafted a sinisterly atheistic view of religious heresy and hypocrisy. The Blood on Satan’s Claw is a delightfully evil mix of Satanic cults, evil witches, and creepy kids. And, thanks to a pair of disturbing scenes in which the coven murders one teenager and rapes another, it’s also a fairly disturbing watch.

The Blood on Satan’s Claw was initially intended to be an anthology movie, with the recurring theme of the rise of Satan tying the whole package together. The three main plotlines – the Judge’s struggle with evil, the possessed fiancée, and the misbehaving school children – were all meant to be separate stories. But with a little massaging by Haggard and Wynne-Simmons, plus the addition of a handful of recurring characters mixed in for continuity, The Blood on Satan’s Claw became one cohesive story with several distinct threads. Nothing brings a movie together quite like the Devil.

Despite the Satanic themes of the movie, the special effects makeup work in The Blood on Satan’s Claw is almost laughable. The titular claw is a furry arm with long ivory fingernails, and it shows up anywhere it can, from peeking out of Rosalyn’s sleeve when she is first possessed to prowling under the floorboards of her room when Peter goes to investigate. Reverend Fallowfield’s students all find themselves with similar hairy spots on their bodies, sort of like furry marks-of-the-beast, one of which is surgically removed by a doctor (played by Howard Goorney from Fiddler on the Roof) in a scene which basically looks like he is peeling off the fuzzy prosthetic makeup application after making his cuts (which is probably what was really happening on set). While the actual Satan’s claw and marks of the beast are noticeably silly, they do help to keep the movie grounded. They’re campy enough to remind the viewer that “it’s only a movie!”

The Hammer Horror influence is particularly strong in The Blood on Satan’s Claw’s photography. Cinematographer Dick Bush (Phase IV, The Legacy) uses a very neutral color palette, heavy on the whites, greys, and browns. The movie is a period piece set in 17th century England, so the drab color scheme works, particularly when there is a bright splash of technicolor, some blood for example, to liven things up. Bush’s camera always feels like its peering in on the characters and situations, showing the events from almost hidden angles or tromping along anonymously with a crowd of spectators, always capturing scenes that aren’t supposed to be captured. It’s a voyeuristic style of cinematography, and it makes the movie all the creepier.

The score is another aspect of The Blood on Satan’s Claw that is particularly Hammer-esque. The music, composed by Marc Wilkinson (If…, The Quatermass Conclusion), is suitably melodramatic, full of gaudy flourishes and suspenseful crescendos. Parts of it even venture into sonic sci-fi territory with spooky Theremins and eerie Moogs. It’s an over-the-top score for an over-the-top movie, technically proficient, yet charming in its bombast.

Folk Horror is a vague and ambiguous subgenre. It’s difficult to pin down exactly what its ingredients include. But whatever it is that makes up Folk Horror, The Blood on Satan’s Claw has it.