The Most Influential Movie of the 20th Century, The Blair Witch Project Turns 20

In 1999, two film students named Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sanchez changed the landscape of horror cinema with The Blair Witch Project.

Every once in a while, a movie comes along that changes the face of the horror landscape. The Exorcist showed people thing that they had never seen in a movie before. Jaws made people afraid of the commonplace. Halloween may not have invented the slasher subgenre, but it most certainly pushed it to the forefront of horror cinema. In 1999, 20 years ago this very week in fact, one of these game changing movies came from out of nowhere to revitalize the whole genre. That movie is The Blair Witch Project, the most influential movie of the 20th century.

The Blair Witch Project is about three film students – Heather Donahue, Joshua Leonard, and Michael Williams – who are making a documentary about a fabled witch that supposedly lives in the woods of Burkittsville, Maryland, an area that was known as Blair Township during the 18th century New England witch trials. After gathering up a few foreshadow-y interviews with locals who have heard about the legend, the three filmmakers head into the woods to visit some of the important locations in Blair Witch mythology. And they promptly get lost. But being lost is the least of their worries.

When the sun goes down, the group finds themselves being stalked and tormented by an unseen force. At first, it’s just unexplained noises in the dark. Then, the trio starts finding rocks stacked outside their tents and crudely fashioned stickmen hanging from the trees. But the longer the three kids are in the woods, the more threatening the – whatever it is – becomes.

During the summer of 1999, The Blair Witch Project was more than just a movie; it was a pop culture phenomenon. Directors Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez, themselves film students at the time, were inspired by real-life horror documentaries when they came up with the concept.

A title card at the beginning of the film lets the viewer know that the film purports to be the actual footage that was shot by the missing film students which and found a year after they disappeared, so the movie has an air of authenticity right from the very first frame. And even though faux-documentaries had been done in the past with movies like Cannibal Holocaust and The Legend of Boggy Creek, there was something different about The Blair Witch Project. It seemed more real. More believable.

The Blair Witch Project Marketing Helps Earn Its Spot as the Most Influential Movie of the 20th Century

A big part of that believability was thanks to the genius marketing of the film. Months before The Blair Witch Project was released, a website was launched which told the story of the mysterious disappearances of Heather, Josh, and Mike. The website, found at www.blairwitch.com, never tipped the visitor off to the fact that the movie was fake (those who happened upon the website for the filmmakers’ production company, Haxan Films, were let in on the secret), so anyone who wound up reading the story and viewing the handful of clips was convinced that the movie was a glorified snuff film. And the morbid curiosity intrigued the hell out of them.

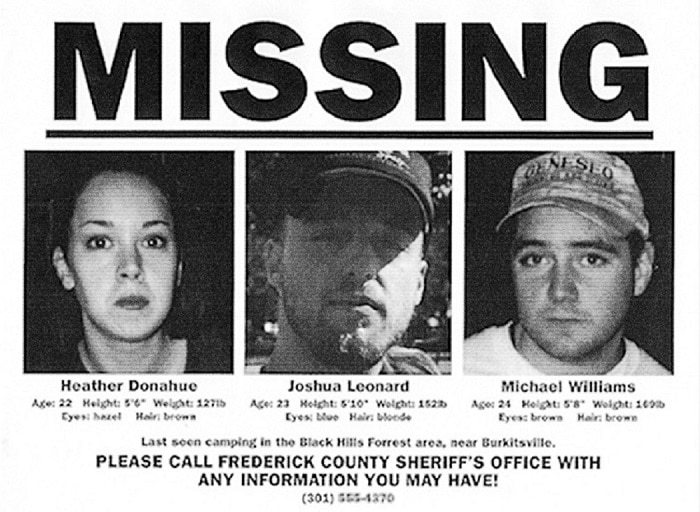

But the viral marketing didn’t stop at the website. Missing persons leaflets were distributed as promotional materials for the film. Taking a page out of the Cannibal Holocaust playbook, Donahue, Leonard, and Williams (all of whom appear in the film under their real names, essentially playing “themselves”) were directed to not do any press appearances or conduct any interviews – basically, they were asked to disappear from the limelight, at least until the film’s secret was eventually revealed.

For a while, the three actors’ IMDB pages had them listed as deceased, and their families reportedly even started getting condolences cards from acquaintances who had presumed them to be dead. While Myrick and Sánchez didn’t get pulled into court like Ruggero Deodato to prove that no one had been killed, the marketing was almost too effective. But it got people to see the movie, enabling it to change the future of horror cinema and become the most influential movie of the 20th century.

Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez created an entire rich mythology at which the movie itself only hinted. A few days before the release of The Blair Witch Project, an hour-long television documentary called Curse of the Blair Witch aired on the Sci-Fi Channel. The special, which was written and directed by Myrick and Sánchez, delved into the backstory behind the legend, including a series of disappearances in Blair Township that were blamed on a witch named Elly Kedward, as well as the misdeeds of a child killer named Rustin Parr who prowled the woods 150 years later. The pre-release exposition served not only to fill in the gaps of the story, but it also generated genuine excitement for the film’s release.

The authenticity of The Blair Witch Project was also aided by the lo-fi, run-and-gun visual style – what is referred to today by nauseous viewers as “shaky cam.” Most of the movie was shot by Donahue, Leonard, and Williams themselves, who were actually sent out into the woods to camp for eight days. The directors would leave supplies and instructions at drop sites, and if the actors missed something important, like a stack of rocks or one of the movie’s trademark stick figures, they could be contacted and sent to the location of the set piece.

They were also tipped off as to when it would be their last night in the woods, which led to Heather Donahue’s famous (and infamous) confession scene. But for the most part, the three actors were on their own. They had a 16mm film camera and a Hi8 video camera, so there are two different looks to the film, but it’s all amateur spastic camera work that, whether by design or by accident, gets more inconsistent as the characters get more exhausted and agitated. The Blair Witch Project almost seems like a film school experiment, but as such, it was a very successful one – the movie was made for about $60,000, and it generated almost $250 million.

Because The Blair Witch Project made so much money on such a meager budget, it opened the floodgates for hundreds of other found footage horror films to be made. This became a double-edged sword, because some of the movies, like the Paranormal Activity series or the Creep movies, were well thought out and used the aesthetic in a genuinely horrifying way, but most of the time, the found footage trend was just a way to save money. And for every faux-documentary horror film that was good, there were 10 bad ones. At least. But they kept coming, because they could be produced so cheaply. Literally anyone could make a found footage movie. And most people did. In this way, The Blair Witch Project is probably the most influential movie of the 20th century.

As a movie, The Blair Witch Project is forgettable. It’s got creepy moments, but much of it resembles home movies, boring at its best and downright annoying at its worst. It needs the mythology and backstory to be effective, and the fact that Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez went to such great lengths to craft the history shows that they realized that. It’s sort of like an alternative reality game, with the movie itself being the payoff. Once the disturbing backstory is told, the average movie becomes a horrifying experience, and one that only lets up after the viewer does even more research and learns that the whole thing was fabricated. But getting to that point is one hell of a rush.

Since its release, The Blair Witch Project has spawned a pair of sequels: The underrated Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2 and the almost-close-enough-to-be-a-remake Blair Witch. But as hard as filmmakers try, there will never be another The Blair Witch Project. Audiences are too suspicious and savvy to completely buy into the found footage genre again. Which is understandable (fool me once, shame on me…), but also kind of a downer. Because the phenomenon of The Blair Witch Project was a lot of fun for those who were tricked by it.