Cinema Fearité presents '11:14'

Director Greg Marcks plays with traditional narrative structure in the brilliant '11:14.'

When done right, playing with a non-linear timeline can be an extremely effective cinematic storytelling tool. Pulp Fiction uses the jump around narrative ingeniously. Memento unfolds in reverse, a technique that works wonderfully in the context of a main character with short-term amnesia. The Butterfly Effect teleports in time as the hero changes his past and, therefore, his future. In 2003, the movie 11:14 also played with the linear timeline by showing the viewer many sides to the same story, all leading up to the same tragic event.

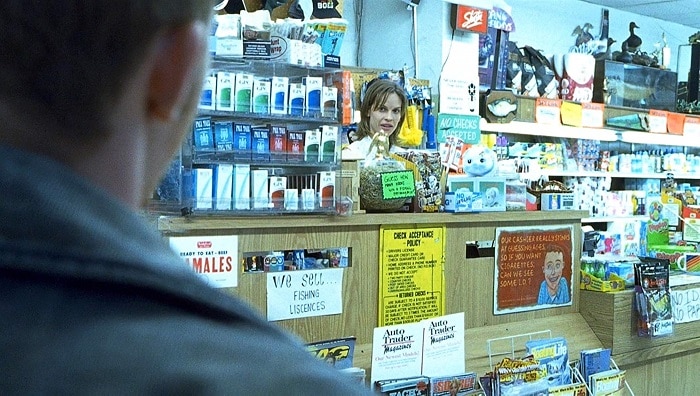

11:14 follows the exploits of a bunch of different people over the course of one fateful evening in the town of Middleton. There’s Jack (Henry Thomas from Ouija: Origin of Evil), who gets into a car accident while driving drunk and talking on his cell phone. There’s also Mark (Elvis & Nixon’s Colin Hanks), Eddie (Hell or High Water’s Ben Foster), and Tim (Stark Sands from Inside Llewyn Davis), a trio of teens who are out cruising around in their parents’ minivan causing mischief. Meanwhile, over at the local convenience store, an employee named Duffy (Shawn Hatosy from The Faculty) has a problem, and the only person who can help him out is his friend and fellow employee Buzzy (The Homesman’s Hilary Swank). Speaking of problems, Duffy’s girlfriend, Cheri (Rachael Leigh Cook from Josie and the Pussycats), has one of her own, and her father, Frank (Road House’s Patrick Swayze), takes it upon himself to solve it for her. And all of their paths meet up at the unlikely time of 11:14 pm.

Written and directed by Greg Marcks (Echelon Conspiracy), 11:14 is an expertly crafted narrative of interweaving stories and entwined characters. The timeline jumps are not jarring at all once the viewer realizes that it’s a plot device. Information is provided slowly and deliberately, the audience given information that they need to know right then, with other bits of exposition held back for later. Marcks shows the bodies, then reveals what happened to them later on, so that all of the pieces of the puzzle fall into place as the events of the night are revisited, one shocked and gasping character at a time. 11:14 is a remarkable feat of twisting and turning storytelling.

As one might have noticed from the synopsis, the cast in 11:14 is a star-studded mixture of established stars and then-promising up-and-comers. Of course, Hilary Swank had already won the first of her two Oscars by then for Boys Don’t Cry, and Patrick Swayze and Henry Thomas were pretty much household names thanks to Ghost and E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, respectively. Shawn Hatosy and Rachael Leigh Cook were familiar to fans of teen movies as well because of Down to You and She’s All That. But Colin Hanks was just Tom Hanks’ son at this point, and Stark Sands and Ben Foster were just kids with bright futures. Other veteran actors like Barbara Hershey (Insidious) and Clark Gregg (The Avengers), as well as additional newcomers like Blake Heron (We Were Soldiers), Jason Segal (“How I Met Your Mother”), and Rick Gomez (The Apparition) round out the “they’re in this movie!” cast. 11:14 boasts a smorgasbord ensemble of familiar faces.

Because it takes place at night, 11:14 is a very dark movie, not just thematically, but photographically. Cinematographer Shane Hurlbut (The Skulls, Terminator Salvation) opens up his camera aperture wide so that the viewer can see everything in each shot, even though it’s all shrouded in darkness. Even during scenes that take place indoors, such as inside the convenience store or in Cheri’s parents’ living room, the lighting is harsh and florescent, giving the movie a dirty, gritty look. Hurlbut also places his camera in unique areas such as on the ground or in car trunks, so the angles are just as interesting as the lighting. Hurlbut’s photography in 11:14 is every bit as inventive as Marcks’ narrative structure.

Speaking of Marcks’ narrative structure, the incongruous timeline in 11:14 means that the editing is of the utmost importance to the continuity of the film. Editors Richard Nord (The Rage: Carrie 2, The Watcher) and Dan Lebental (Marvel movies like Iron Man, Ant-Man, and Spider-Man: Far From Home) earn their money with this one. Not only do they have to keep the four or five different timelines straight, but they must also skillfully traverse the segments where the action intersects, making sure to show enough to let the viewer know what’s happening without giving away any of the big secrets that have not been told yet. It’s the perfect blend of editing for continuity and editing for effect, and it does it all without stepping all over itself.

The music for 11:14 was composed by Clint Mansell, who was the frontman and primary songwriter for British alternative rock band Pop Will Eat Itself before going on to score movies like Darren Aronofsky’s Requiem for a Dream and Black Swan, as well as Park Chan-wook’s Stoker and Ben Wheatley’s High-Rise. Mansell’s music for 11:14 is a quirky combination of an orchestral cinematic score and a pulsing electronic soundtrack, with just enough pop sensibility and catchy hum-a-long hooks to be memorable. The score is dated, obviously from the early 21st century, but that’s what a movie like 11:14 needs. And that’s what Mansell provides in spades.

They say the shortest distance between two points is a straight line. But sometimes, the most effective way to get from point A to point B takes a few turns. And 11:14 pilots through those turns perfectly.