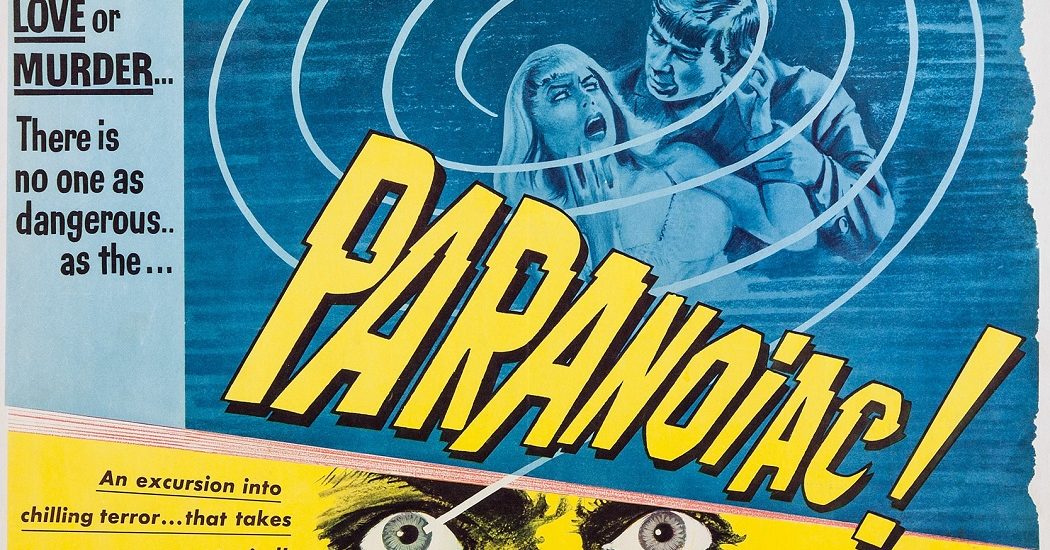

Cinema Fearité presents 'Paranoiac'

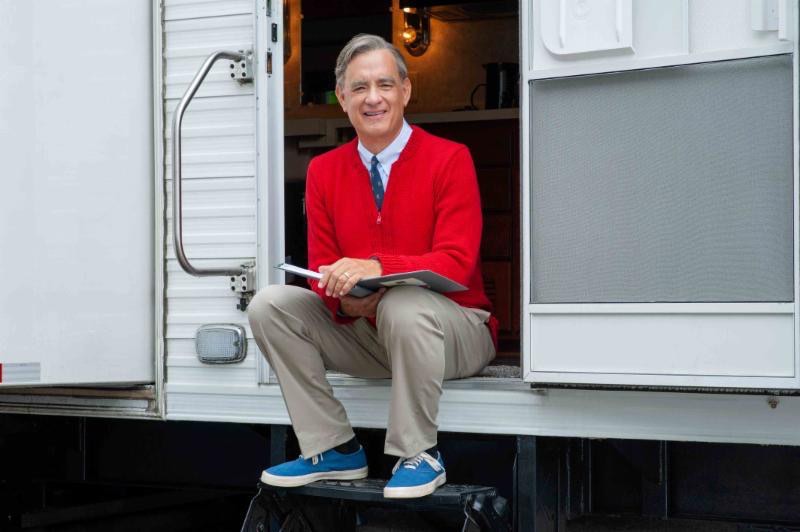

Freddie Francis and Jimmy Sangster team up for 'Paranoiac,' a Hammer homage to 'Psycho.'

In the years after Alfred Hitchcock’s influential 1960 masterpiece Psycho, filmmakers everywhere rushed to pump out exploitive little horror movies dealing with the mentally unhinged, most with similar one-word titles. William Castle did Homicidal and Strait-Jacket. Roman Polanski stormed in with Repulsion. Hammer Film Productions seemed to try a new one every year, releasing movies like Maniac, Nightmare, Hysteria, Fanatic…and the subject of this week’s Cinema Fearité column, 1963’s Paranoiac.

Paranoiac revolves around the children of the Ashby family as they deal with the deaths of their parents eleven years earlier. While Simon (Oliver Reed from The Devils, The Brood, and Burnt Offerings), a broke alcoholic, only cares about getting his hands on the inheritance that will inevitably be his, the emotionally fragile Eleanor (Janette Scott from Invasion of the Triffids) grieves for the loss of their other brother, Tony, who committed suicide in the wake of their parents’ tragedy.

When Tony (Alexander Davion from Valley of the Dolls) randomly shows back up at the family home, alarms go off with Simon and the protective Aunt Harriet (Afraid of the Dark’s Sheila Burrell), the two thinking that a con man is in their midst. Eleanor, however, desperately wants to believe that it really is Tony. Simon, thinking that the new arrival is after his money, intends to prove that “Tony” is not their brother, and he’ll go to great lengths to do so.

When it came to the Hammer psychological horror films, there was no tandem quite like director Freddie Francis (Tales from the Crypt, The Deadly Bees) and screenwriter Jimmy Sangster (The Snorkel, Jack the Ripper, Scream of Fear), and that’s who’s at the controls of Paranoiac. Like the other Hammer movies of the time, Paranoiac was an attempt to capture the aesthetic look and feel of Psycho while still being its own original entity. And for the most part, it’s successful at that mission.

It’s difficult to tell who the antagonist is in Paranoiac. Or, to be more specific, there are more than one potential antagonists in the film. The obvious one is Simon, whose drunken shenanigans coupled with his financial desperation cause him to try to purposely exploit his sister’s fragile psyche to enrich himself. Then there’s Tony, a character who may or may not be who he is pretending to be (SPOILER ALERT – he’s not).

Finally, there’s the mysterious masked maniac who stalks and kills people with a fisherman’s hand hook. And, on a lesser scale, the nurse that Simon has hired for Eleanor is not really a nurse, but a bombshell named Francoise (Maniac’s Liliane Brousse) with whom he is having an affair. Honestly, the trusting Eleanor is the only truly sympathetic character in the entire movie.

Cinematographer Arthur Grant (The Witches, The Abominable Snowman) lets the audience know who he thinks is the antagonist, though. Like many of the other Psycho homages of the sixties, Paranoiac was shot in high-contrast black and white, allowing Grant to use shadows and light to give the film a grimy, noir look. Whenever Grant shoots Simon, his camera captures the man angrily, always with either a menacing sneer or a sarcastic grimace.

Part of it is Oliver Reed’s committed performance, but much of it is the drunkenly furious approach that Grant takes to presenting the character. Arthur Grant knows who he thinks the bad guy is, and he shares that information with the audience through his camera lens.

Paranoiac has a score, too. And it’s a horror score. It sounds very much like the scores from all of the other Hammer psychological thrillers of the time. It was composed by Elisabeth Lutyens (The Earth Dies Screaming, Never Take Sweets from a Stranger), and it’s full of swelling orchestral movements and stinging string stabs. It’s well-written and effective, but not very memorable. In fact, one could probably interchange it with the soundtrack for, say, Nightmare (another Francis/Sangster joint from the next year), and both movie-and-score combinations would be right at home. Nothing wrong with that, but it does sound like a formula.

It’s been said that Psycho is one of the most influential movies of all time, but what isn’t said as much is how instantaneous that influence was. Paranoiac may not be the best of the direct line of Psycho imitators to have been made in the early sixties, but you could do worse. A lot worse.