With roots that stem from various mythologies as opposed to any single source, the werewolf has been depicted in many different ways over the history of cinema. From the silent classic Wolf Blood to the teen romance Twilight series, werewolves have been brought to the screen by both costumed actors and CGI artists. Seemingly every studio and director has had their own individual take on lycanthropy. Even Amicus Productions, the British studio that was mainly known for its anthology films, got into the werewolf act in 1974 with The Beast Must Die.

The Beast Must Die is about a millionaire named Tom Newcliffe (Calvin Lockhart from Wild at Heart) who invites a group of people up to his country estate to spend the weekend of the full moon with him and his wife, Caroline (Marlene Clark from Ganja & Hess). Among the guests is a lycanthropy expert named Dr. Christopher Lundgren (Hammer Horror icon Peter Cushing, most known for his role of Grand Moff Tarkin in Star Wars), a famous pianist named Jan Jarmokowski (Michael Gambon, better known as Dumbledore from the Harry Potter movies), his ex-student and now wife Davina (Ciaran Madden from Swing Kids), an artist named Paul Foot (Tom Chadbon from Tess), and a diplomat named Arthur Bennington (Charles Gray from The Rocky Horror Picture Show and The Legacy). Once the guests arrive and have met, Tom reveals that one of them is a werewolf, and he intends to expose the beast and hunt it until it is killed. With help from his assistant, Pavel (Where Eagles Dare’s Anton Diffring), Tom puts the group through test after test, hoping to induce the werewolf into transforming. Eventually, the wolf does show up, but only to kill Tom’s servants and guests, and always escaping before he can determine its identity. Nevertheless, Tom stays resolved to flush out the culprit and kill the beast.

The Beast Must Die is a pretty clever movie. Directed by Paul Annett (Tales of the Unexpected) and written by Michael Winder (The Diamond Mercenaries), it’s a mish-mash of several different genres. It’s a horror movie. It’s an action movie. It’s a mystery. The character of Tom Newcliffe being African-American even lends a Blaxploitation-esque element to the film. Even with the crossing of styles, the film is not schizophrenic or confused; as a movie, The Beast Must Die works wonderfully well.

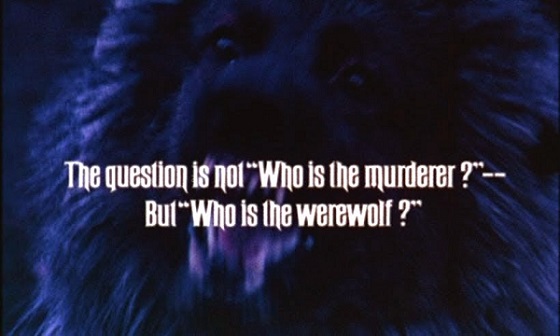

There is a William Castle-esque gimmick to The Beast Must Die that makes it both fun and memorable. At its beginning, the film invites the viewer to become an active participant in the werewolf search, stating that “You are the detective!” and asking “Who is the werewolf?”, warning the audience that all of the clues will be given and they will have a chance to solve the mystery by the end. Right before the third act, there is a “werewolf break,” a brief pause in the movie during which the viewer is given thirty seconds to decide who they think the werewolf is before the secret is revealed. It’s a fun way to involve the audience, and this “werewolf break” is what viewers usually remember most about The Beast Must Die.

The werewolf in The Beast Must Die is played by an actual canine; a large German Shepherd dressed in longer, darker fur was used in most scenes. For some close-ups and action scenes, the wolf appears to be a puppet or dummy, but for most of the movie it’s the trained dog doing the running and stalking. It’s not quite as traditional as the anthropomorphic wolf-man model that is used in most werewolf movies, but the ferocity of the dog itself is terrifying, so it actually ends up being more effective in terms of creating scares. Of course, when the culprit is finally revealed, there is a classic werewolf stop-motion transformation from beast to man, but for the majority of the film, the Beast is a big, scary dog.

Photographically, the look of The Beast Must Die is a cool hybrid of horror movie and action thriller. Shot by experienced cinematographer Jack Hildyard (The Bridge on the River Kwai), the film has the obvious Technicolor tone of a seventies British horror film, but it breaks out of that mold when Tom stalks his prey. The hunt scenes are reminiscent of a James Bond-type of spy movie, with plenty of suspenseful chases that Hildyard captures with fluid camera work, tossing the viewer into the middle of the search. Visually, the film is as beautiful as anything that Amicus made in the seventies, with lots of striking colors barely contained by the soft filters of fog and mist. Photographically, The Beast Must Die looks great.

Just like the cinematography, the music for The Beast Must Die walks the line between horror and action. The score was written by Douglas Gamley (who did many Amicus films, including Tales from the Crypt, Asylum, and The Vault of Horror), and it’s full of typical horror stingers and musical beds that ramp up the suspense. When it gets to the action scenes, the soundtrack switches to a funky, seventies spy-jam type of sound, somewhat reinforcing the Blaxploitation elements of the film. It’s an interesting choice, making the hunts more of an adrenaline rush than a heart-pounding journey. Nevertheless, Gamley’s score for The Beast Must Die is unlike the score to any other horror movie; it’s got soul.

Although they often find their way into other genres like comedy or romance, werewolves have always been a staple of horror movies. For those who are wanting a werewolf movie with a twist or two, the search is over; look no further than The Beast Must Die.